Simple app state management

Now that you know about declarative UI programming and the difference between ephemeral and app state, you are ready to learn about simple app state management.

On this page, we are going to be using the provider package.

If you are new to Flutter and you don’t have a strong reason to choose

another approach (Redux, Rx, hooks, etc.), this is probably the approach

you should start with. The provider package is easy to understand

and it doesn’t use much code.

It also uses concepts that are applicable in every other approach.

That said, if you have a strong background in state management from other reactive frameworks, you can find packages and tutorials listed on the options page.

Our example

For illustration, consider the following simple app.

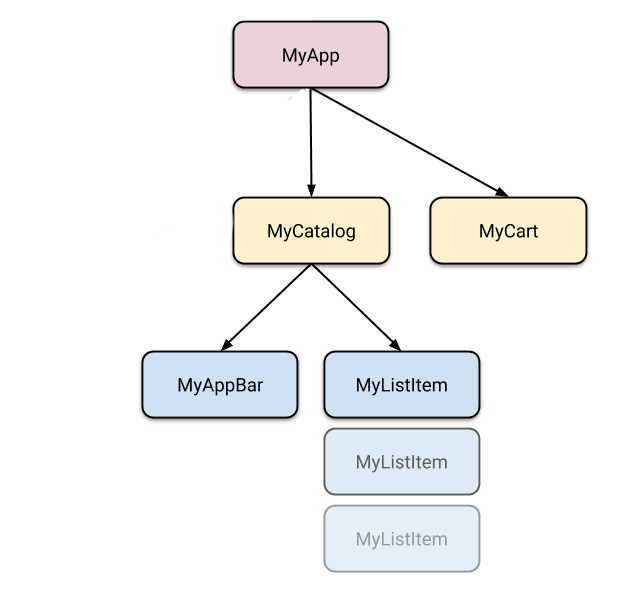

The app has two separate screens: a catalog,

and a cart (represented by the MyCatalog,

and MyCart widgets, respectively). It could be a shopping app,

but you can imagine the same structure in a simple social networking

app (replace catalog for “wall” and cart for “favorites”).

The catalog screen includes a custom app bar (MyAppBar)

and a scrolling view of many list items (MyListItems).

Here’s the app visualized as a widget tree.

So we have at least 5 subclasses of Widget. Many of them need

access to state that “belongs” elsewhere. For example, each

MyListItem needs to be able to add itself to the cart.

It might also want to see whether the currently displayed item

is already in the cart.

This takes us to our first question: where should we put the current state of the cart?

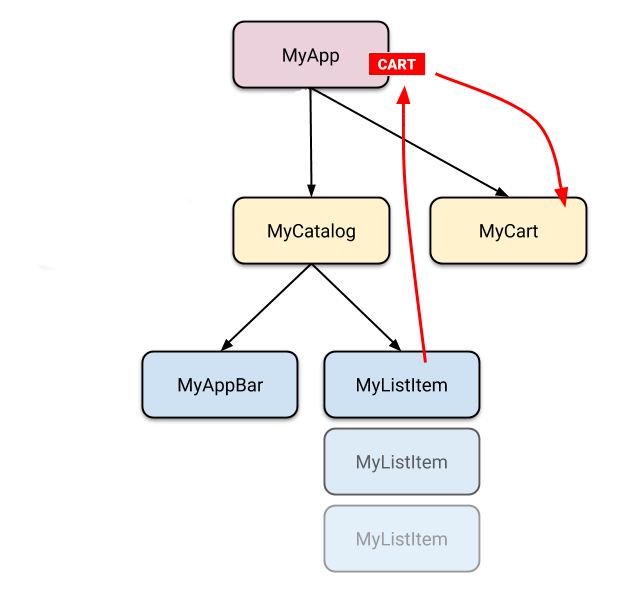

Lifting state up

In Flutter, it makes sense to keep the state above the widgets that use it.

Why? In declarative frameworks like Flutter, if you want to change the UI,

you have to rebuild it. There is no easy way to have

MyCart.updateWith(somethingNew). In other words, it’s hard to

imperatively change a widget from outside, by calling a method on it.

And even if you could make this work, you would be fighting the

framework instead of letting it help you.

// BAD: DO NOT DO THIS

void myTapHandler() {

var cartWidget = somehowGetMyCartWidget();

cartWidget.updateWith(item);

}

Even if you get the above code to work,

you would then have to deal

with the following in the MyCart widget:

// BAD: DO NOT DO THIS

Widget build(BuildContext context) {

return SomeWidget(

// The initial state of the cart.

);

}

void updateWith(Item item) {

// Somehow you need to change the UI from here.

}

You would need to take into consideration the current state of the UI and apply the new data to it. It’s hard to avoid bugs this way.

In Flutter, you construct a new widget every time its contents change.

Instead of MyCart.updateWith(somethingNew) (a method call)

you use MyCart(contents) (a constructor). Because you can only

construct new widgets in the build methods of their parents,

if you want to change contents, it needs to live in MyCart’s

parent or above.

// GOOD

void myTapHandler(BuildContext context) {

var cartModel = somehowGetMyCartModel(context);

cartModel.add(item);

}Now MyCart has only one code path for building any version of the UI.

// GOOD

Widget build(BuildContext context) {

var cartModel = somehowGetMyCartModel(context);

return SomeWidget(

// Just construct the UI once, using the current state of the cart.

// ···

);

}In our example, contents needs to live in MyApp. Whenever it changes,

it rebuilds MyCart from above (more on that later). Because of this,

MyCart doesn’t need to worry about lifecycle—it just declares

what to show for any given contents. When that changes, the old

MyCart widget disappears and is completely replaced by the new one.

This is what we mean when we say that widgets are immutable. They don’t change—they get replaced.

Now that we know where to put the state of the cart, let’s see how to access it.

Accessing the state

When a user clicks on one of the items in the catalog,

it’s added to the cart. But since the cart lives above MyListItem,

how do we do that?

A simple option is to provide a callback that MyListItem can call

when it is clicked. Dart’s functions are first class objects,

so you can pass them around any way you want. So, inside

MyCatalog you can define the following:

@override

Widget build(BuildContext context) {

return SomeWidget(

// Construct the widget, passing it a reference to the method above.

MyListItem(myTapCallback),

);

}

void myTapCallback(Item item) {

print('user tapped on $item');

}This works okay, but for an app state that you need to modify from many different places, you’d have to pass around a lot of callbacks—which gets old pretty quickly.

Fortunately, Flutter has mechanisms for widgets to provide data and

services to their descendants (in other words, not just their children,

but any widgets below them). As you would expect from Flutter,

where Everything is a Widget™, these mechanisms are just special

kinds of widgets—InheritedWidget, InheritedNotifier,

InheritedModel, and more. We won’t be covering those here,

because they are a bit low-level for what we’re trying to do.

Instead, we are going to use a package that works with the low-level

widgets but is simple to use. It’s called provider.

Before working with provider,

don’t forget to add the dependency on it to your pubspec.yaml.

name: my_name

description: Blah blah blah.

# ...

dependencies:

flutter:

sdk: flutter

provider: ^6.0.0

dev_dependencies:

# ...

Now you can import 'package:provider/provider.dart';

and start building.

With provider, you don’t need to worry about callbacks or

InheritedWidgets. But you do need to understand 3 concepts:

- ChangeNotifier

- ChangeNotifierProvider

- Consumer

ChangeNotifier

ChangeNotifier is a simple class included in the Flutter SDK which provides

change notification to its listeners. In other words, if something is

a ChangeNotifier, you can subscribe to its changes. (It is a form of

Observable, for those familiar with the term.)

In provider, ChangeNotifier is one way to encapsulate your application

state. For very simple apps, you get by with a single ChangeNotifier.

In complex ones, you’ll have several models, and therefore several

ChangeNotifiers. (You don’t need to use ChangeNotifier with provider

at all, but it’s an easy class to work with.)

In our shopping app example, we want to manage the state of the cart in a

ChangeNotifier. We create a new class that extends it, like so:

class CartModel extends ChangeNotifier { /// Internal, private state of the cart. final List<Item> _items = []; /// An unmodifiable view of the items in the cart. UnmodifiableListView<Item> get items => UnmodifiableListView(_items); /// The current total price of all items (assuming all items cost $42). int get totalPrice => _items.length * 42; /// Adds [item] to cart. This and [removeAll] are the only ways to modify the /// cart from the outside. void add(Item item) { _items.add(item); // This call tells the widgets that are listening to this model to rebuild. notifyListeners(); } /// Removes all items from the cart. void removeAll() { _items.clear(); // This call tells the widgets that are listening to this model to rebuild. notifyListeners(); } }

The only code that is specific to ChangeNotifier is the call

to notifyListeners(). Call this method any time the model changes in a way

that might change your app’s UI. Everything else in CartModel is the

model itself and its business logic.

ChangeNotifier is part of flutter:foundation and doesn’t depend on

any higher-level classes in Flutter. It’s easily testable (you don’t even need

to use widget testing for it). For example,

here’s a simple unit test of CartModel:

test('adding item increases total cost', () {

final cart = CartModel();

final startingPrice = cart.totalPrice;

cart.addListener(() {

expect(cart.totalPrice, greaterThan(startingPrice));

});

cart.add(Item('Dash'));

});ChangeNotifierProvider

ChangeNotifierProvider is the widget that provides an instance of

a ChangeNotifier to its descendants. It comes from the provider package.

We already know where to put ChangeNotifierProvider: above the widgets that

need to access it. In the case of CartModel, that means somewhere

above both MyCart and MyCatalog.

You don’t want to place ChangeNotifierProvider higher than necessary

(because you don’t want to pollute the scope). But in our case,

the only widget that is on top of both MyCart and MyCatalog is MyApp.

void main() {

runApp(

ChangeNotifierProvider(

create: (context) => CartModel(),

child: const MyApp(),

),

);

}Note that we’re defining a builder that creates a new instance

of CartModel. ChangeNotifierProvider is smart enough not to rebuild

CartModel unless absolutely necessary. It also automatically calls

dispose() on CartModel when the instance is no longer needed.

If you want to provide more than one class, you can use MultiProvider:

void main() {

runApp(

MultiProvider(

providers: [

ChangeNotifierProvider(create: (context) => CartModel()),

Provider(create: (context) => SomeOtherClass()),

],

child: const MyApp(),

),

);

}Consumer

Now that CartModel is provided to widgets in our app through the

ChangeNotifierProvider declaration at the top, we can start using it.

This is done through the Consumer widget.

return Consumer<CartModel>(

builder: (context, cart, child) {

return Text("Total price: ${cart.totalPrice}");

},

);We must specify the type of the model that we want to access.

In this case, we want CartModel, so we write

Consumer<CartModel>. If you don’t specify the generic (<CartModel>),

the provider package won’t be able to help you. provider is based on types,

and without the type, it doesn’t know what you want.

The only required argument of the Consumer widget

is the builder. Builder is a function that is called whenever the

ChangeNotifier changes. (In other words, when you call notifyListeners()

in your model, all the builder methods of all the corresponding

Consumer widgets are called.)

The builder is called with three arguments. The first one is context,

which you also get in every build method.

The second argument of the builder function is the instance of

the ChangeNotifier. It’s what we were asking for in the first place.

You can use the data in the model to define what the UI should look like

at any given point.

The third argument is child, which is there for optimization.

If you have a large widget subtree under your Consumer

that doesn’t change when the model changes, you can construct it

once and get it through the builder.

return Consumer<CartModel>( builder: (context, cart, child) => Stack( children: [ // Use SomeExpensiveWidget here, without rebuilding every time. if (child != null) child, Text("Total price: ${cart.totalPrice}"), ], ), // Build the expensive widget here. child: const SomeExpensiveWidget(), );

It is best practice to put your Consumer widgets as deep in the tree

as possible. You don’t want to rebuild large portions of the UI

just because some detail somewhere changed.

// DON'T DO THIS

return Consumer<CartModel>(

builder: (context, cart, child) {

return HumongousWidget(

// ...

child: AnotherMonstrousWidget(

// ...

child: Text('Total price: ${cart.totalPrice}'),

),

);

},

);Instead:

// DO THIS

return HumongousWidget(

// ...

child: AnotherMonstrousWidget(

// ...

child: Consumer<CartModel>(

builder: (context, cart, child) {

return Text('Total price: ${cart.totalPrice}');

},

),

),

);Provider.of

Sometimes, you don’t really need the data in the model to change the

UI but you still need to access it. For example, a ClearCart

button wants to allow the user to remove everything from the cart.

It doesn’t need to display the contents of the cart,

it just needs to call the clear() method.

We could use Consumer<CartModel> for this,

but that would be wasteful. We’d be asking the framework to

rebuild a widget that doesn’t need to be rebuilt.

For this use case, we can use Provider.of,

with the listen parameter set to false.

Provider.of<CartModel>(context, listen: false).removeAll();Using the above line in a build method won’t cause this widget to

rebuild when notifyListeners is called.

Putting it all together

You can check out the example covered in this article.

If you want something simpler,

see what the simple Counter app looks like when

built with provider.

By following along with these articles, you’ve greatly

improved your ability to create state-based applications.

Try building an application with provider yourself to

master these skills.