Flutter architectural overview

This article is intended to provide a high-level overview of the architecture of Flutter, including the core principles and concepts that form its design.

Flutter is a cross-platform UI toolkit that is designed to allow code reuse across operating systems such as iOS and Android, while also allowing applications to interface directly with underlying platform services. The goal is to enable developers to deliver high-performance apps that feel natural on different platforms, embracing differences where they exist while sharing as much code as possible.

During development, Flutter apps run in a VM that offers stateful hot reload of changes without needing a full recompile. For release, Flutter apps are compiled directly to machine code, whether Intel x64 or ARM instructions, or to JavaScript if targeting the web. The framework is open source, with a permissive BSD license, and has a thriving ecosystem of third-party packages that supplement the core library functionality.

This overview is divided into a number of sections:

- The layer model: The pieces from which Flutter is constructed.

- Reactive user interfaces: A core concept for Flutter user interface development.

- An introduction to widgets: The fundamental building blocks of Flutter user interfaces.

- The rendering process: How Flutter turns UI code into pixels.

- An overview of the platform embedders: The code that lets mobile and desktop OSes execute Flutter apps.

- Integrating Flutter with other code: Information about different techniques available to Flutter apps.

- Support for the web: Concluding remarks about the characteristics of Flutter in a browser environment.

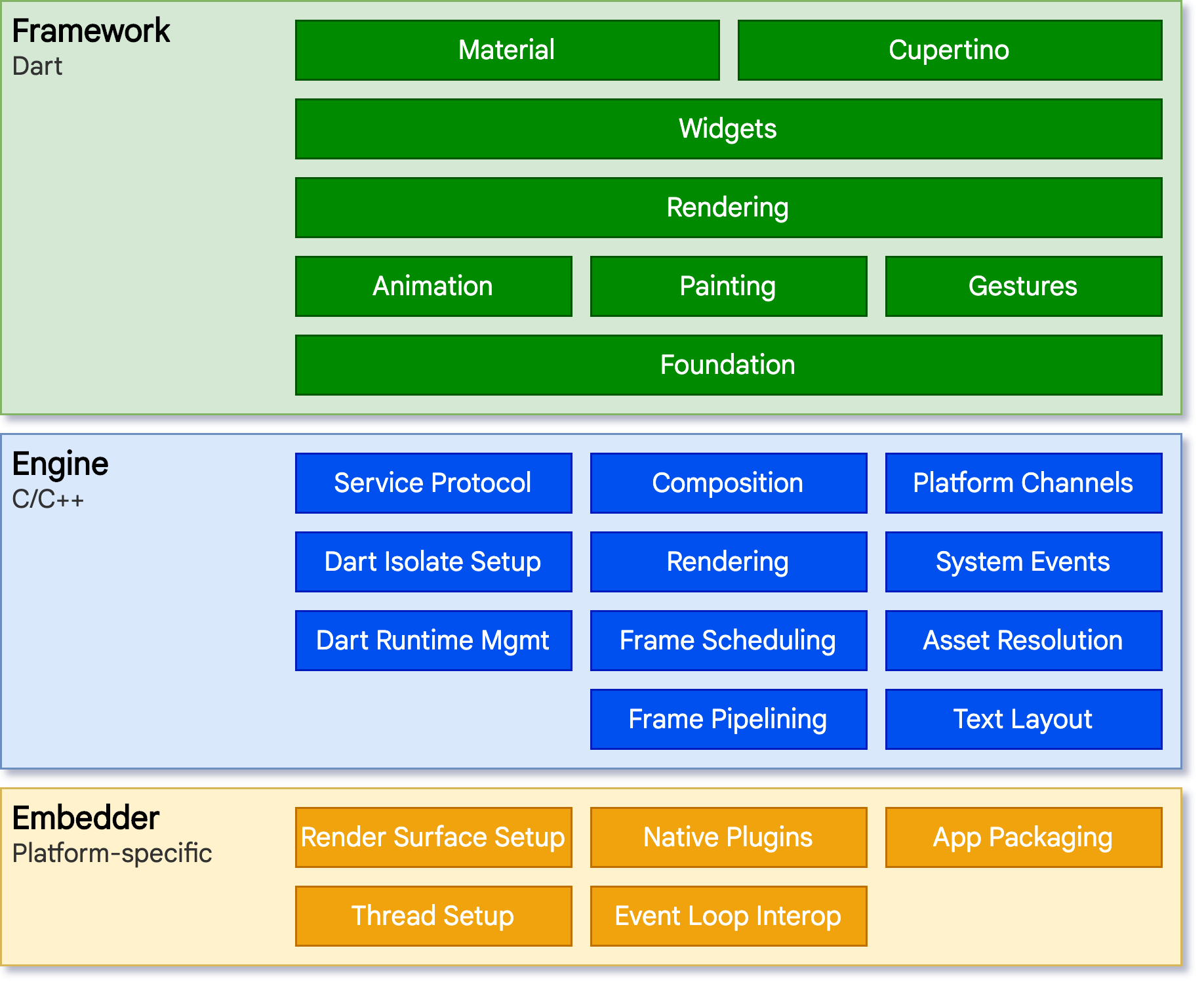

Architectural layers

Flutter is designed as an extensible, layered system. It exists as a series of independent libraries that each depend on the underlying layer. No layer has privileged access to the layer below, and every part of the framework level is designed to be optional and replaceable.

To the underlying operating system, Flutter applications are packaged in the same way as any other native application. A platform-specific embedder provides an entrypoint; coordinates with the underlying operating system for access to services like rendering surfaces, accessibility, and input; and manages the message event loop. The embedder is written in a language that is appropriate for the platform: currently Java and C++ for Android, Objective-C/Objective-C++ for iOS and macOS, and C++ for Windows and Linux. Using the embedder, Flutter code can be integrated into an existing application as a module, or the code may be the entire content of the application. Flutter includes a number of embedders for common target platforms, but other embedders also exist.

At the core of Flutter is the Flutter engine, which is mostly written in C++ and supports the primitives necessary to support all Flutter applications. The engine is responsible for rasterizing composited scenes whenever a new frame needs to be painted. It provides the low-level implementation of Flutter’s core API, including graphics (through Skia), text layout, file and network I/O, accessibility support, plugin architecture, and a Dart runtime and compile toolchain.

The engine is exposed to the Flutter framework through

dart:ui,

which wraps the underlying C++ code in Dart classes. This library

exposes the lowest-level primitives, such as classes for driving input,

graphics, and text rendering subsystems.

Typically, developers interact with Flutter through the Flutter framework, which provides a modern, reactive framework written in the Dart language. It includes a rich set of platform, layout, and foundational libraries, composed of a series of layers. Working from the bottom to the top, we have:

- Basic foundational classes, and building block services such as animation, painting, and gestures that offer commonly used abstractions over the underlying foundation.

- The rendering layer provides an abstraction for dealing with layout. With this layer, you can build a tree of renderable objects. You can manipulate these objects dynamically, with the tree automatically updating the layout to reflect your changes.

- The widgets layer is a composition abstraction. Each render object in the rendering layer has a corresponding class in the widgets layer. In addition, the widgets layer allows you to define combinations of classes that you can reuse. This is the layer at which the reactive programming model is introduced.

- The Material and Cupertino libraries offer comprehensive sets of controls that use the widget layer’s composition primitives to implement the Material or iOS design languages.

The Flutter framework is relatively small; many higher-level features that developers might use are implemented as packages, including platform plugins like camera and webview, as well as platform-agnostic features like characters, http, and animations that build upon the core Dart and Flutter libraries. Some of these packages come from the broader ecosystem, covering services like in-app payments, Apple authentication, and animations.

The rest of this overview broadly navigates down the layers, starting with the reactive paradigm of UI development. Then, we describe how widgets are composed together and converted into objects that can be rendered as part of an application. We describe how Flutter interoperates with other code at a platform level, before giving a brief summary of how Flutter’s web support differs from other targets.

Reactive user interfaces

On the surface, Flutter is a reactive, pseudo-declarative UI framework, in which the developer provides a mapping from application state to interface state, and the framework takes on the task of updating the interface at runtime when the application state changes. This model is inspired by work that came from Facebook for their own React framework, which includes a rethinking of many traditional design principles.

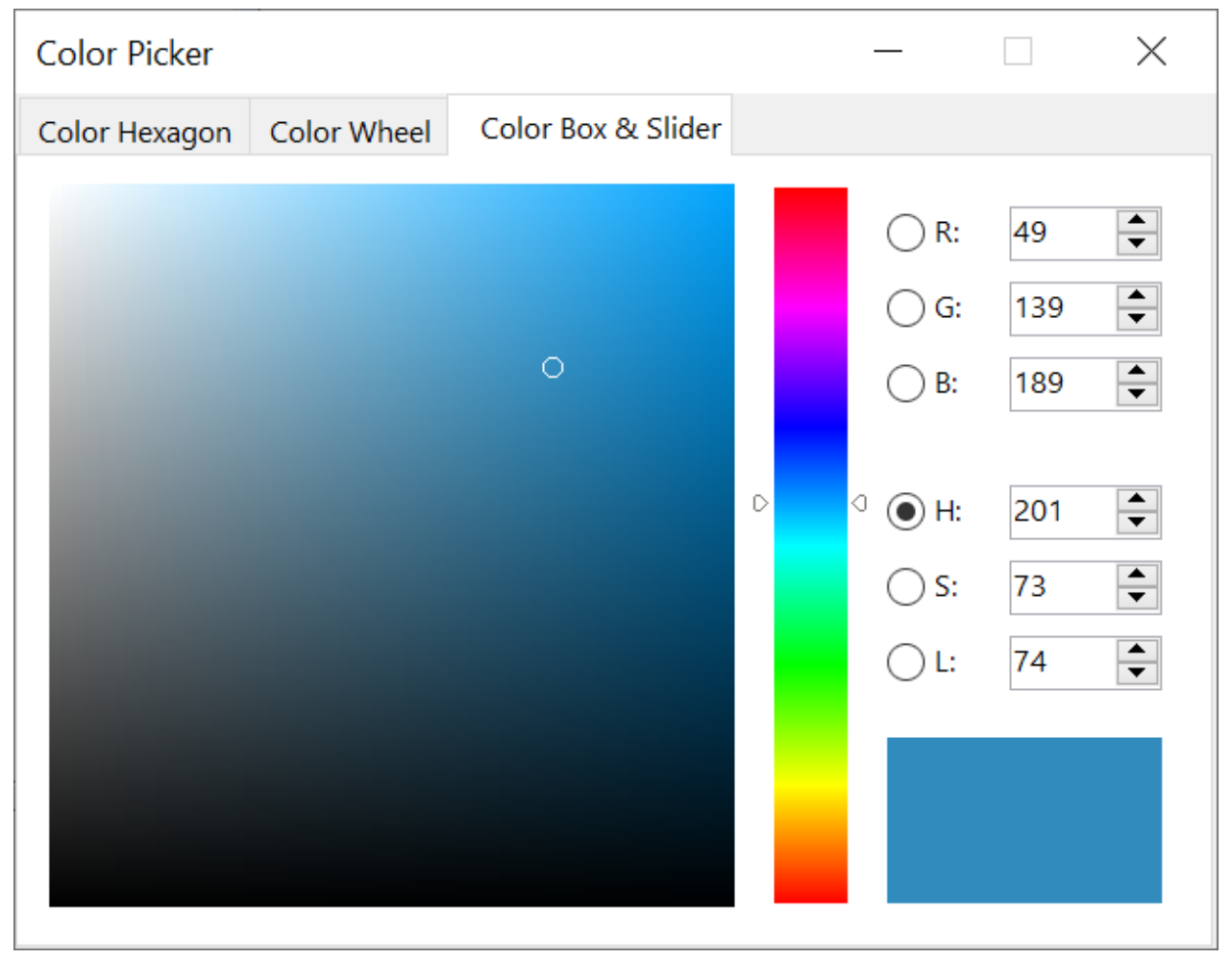

In most traditional UI frameworks, the user interface’s initial state is described once and then separately updated by user code at runtime, in response to events. One challenge of this approach is that, as the application grows in complexity, the developer needs to be aware of how state changes cascade throughout the entire UI. For example, consider the following UI:

There are many places where the state can be changed: the color box, the hue slider, the radio buttons. As the user interacts with the UI, changes must be reflected in every other place. Worse, unless care is taken, a minor change to one part of the user interface can cause ripple effects to seemingly unrelated pieces of code.

One solution to this is an approach like MVC, where you push data changes to the model via the controller, and then the model pushes the new state to the view via the controller. However, this also is problematic, since creating and updating UI elements are two separate steps that can easily get out of sync.

Flutter, along with other reactive frameworks, takes an alternative approach to this problem, by explicitly decoupling the user interface from its underlying state. With React-style APIs, you only create the UI description, and the framework takes care of using that one configuration to both create and/or update the user interface as appropriate.

In Flutter, widgets (akin to components in React) are represented by immutable classes that are used to configure a tree of objects. These widgets are used to manage a separate tree of objects for layout, which is then used to manage a separate tree of objects for compositing. Flutter is, at its core, a series of mechanisms for efficiently walking the modified parts of trees, converting trees of objects into lower-level trees of objects, and propagating changes across these trees.

A widget declares its user interface by overriding the build() method, which

is a function that converts state to UI:

UI = f(state)

The build() method is by design fast to execute and should be free of side

effects, allowing it to be called by the framework whenever needed (potentially

as often as once per rendered frame).

This approach relies on certain characteristics of a language runtime (in particular, fast object instantiation and deletion). Fortunately, Dart is particularly well suited for this task.

Widgets

As mentioned, Flutter emphasizes widgets as a unit of composition. Widgets are the building blocks of a Flutter app’s user interface, and each widget is an immutable declaration of part of the user interface.

Widgets form a hierarchy based on composition. Each widget nests inside its

parent and can receive context from the parent. This structure carries all the

way up to the root widget (the container that hosts the Flutter app, typically

MaterialApp or CupertinoApp), as this trivial example shows:

import 'package:flutter/material.dart';

void main() => runApp(const MyApp());

class MyApp extends StatelessWidget {

const MyApp({Key? key}) : super(key: key);

@override

Widget build(BuildContext context) {

return MaterialApp(

home: Scaffold(

appBar: AppBar(

title: const Text('My Home Page'),

),

body: Center(

child: Builder(

builder: (BuildContext context) {

return Column(

children: [

const Text('Hello World'),

const SizedBox(height: 20),

ElevatedButton(

onPressed: () {

print('Click!');

},

child: const Text('A button'),

),

],

);

},

),

),

),

);

}

}In the preceding code, all instantiated classes are widgets.

Apps update their user interface in response to events (such as a user interaction) by telling the framework to replace a widget in the hierarchy with another widget. The framework then compares the new and old widgets, and efficiently updates the user interface.

Flutter has its own implementations of each UI control, rather than deferring to those provided by the system: for example, there is a pure Dart implementation of both the iOS Switch control and the one for the Android equivalent.

This approach provides several benefits:

- Provides for unlimited extensibility. A developer who wants a variant of the Switch control can create one in any arbitrary way, and is not limited to the extension points provided by the OS.

- Avoids a significant performance bottleneck by allowing Flutter to composite the entire scene at once, without transitioning back and forth between Flutter code and platform code.

- Decouples the application behavior from any operating system dependencies. The application looks and feels the same on all versions of the OS, even if the OS changed the implementations of its controls.

Composition

Widgets are typically composed of many other small, single-purpose widgets that combine to produce powerful effects.

Where possible, the number of design concepts is kept to a minimum while

allowing the total vocabulary to be large. For example, in the widgets layer,

Flutter uses the same core concept (a Widget) to represent drawing to the

screen, layout (positioning and sizing), user interactivity, state management,

theming, animations, and navigation. In the animation layer, a pair of concepts,

Animations and Tweens, cover most of the design space. In the rendering

layer, RenderObjects are used to describe layout, painting, hit testing, and

accessibility. In each of these cases, the corresponding vocabulary ends up

being large: there are hundreds of widgets and render objects, and dozens of

animation and tween types.

The class hierarchy is deliberately shallow and broad to maximize the possible

number of combinations, focusing on small, composable widgets that each do one

thing well. Core features are abstract, with even basic features like padding

and alignment being implemented as separate components rather than being built

into the core. (This also contrasts with more traditional APIs where features

like padding are built in to the common core of every layout component.) So, for

example, to center a widget, rather than adjusting a notional Align property,

you wrap it in a Center

widget.

There are widgets for padding, alignment, rows, columns, and grids. These layout widgets do not have a visual representation of their own. Instead, their sole purpose is to control some aspect of another widget’s layout. Flutter also includes utility widgets that take advantage of this compositional approach.

For example, Container, a

commonly used widget, is made up of several widgets responsible for layout,

painting, positioning, and sizing. Specifically, Container is made up of the

LimitedBox,

ConstrainedBox,

Align,

Padding,

DecoratedBox, and

Transform widgets, as you

can see by reading its source code. A defining characteristic of Flutter is that

you can drill down into the source for any widget and examine it. So, rather

than subclassing Container to produce a customized effect, you can compose it

and other simple widgets in novel ways, or just create a new widget using

Container as inspiration.

Building widgets

As mentioned earlier, you determine the visual representation of a widget by

overriding the

build() function to

return a new element tree. This tree represents the widget’s part of the user

interface in more concrete terms. For example, a toolbar widget might have a

build function that returns a horizontal

layout of some

text and

various

buttons. As needed,

the framework recursively asks each widget to build until the tree is entirely

described by concrete renderable

objects. The

framework then stitches together the renderable objects into a renderable object

tree.

A widget’s build function should be free of side effects. Whenever the function is asked to build, the widget should return a new tree of widgets1, regardless of what the widget previously returned. The framework does the heavy lifting work to determine which build methods need to be called based on the render object tree (described in more detail later). More information about this process can be found in the Inside Flutter topic.

On each rendered frame, Flutter can recreate just the parts of the UI where the

state has changed by calling that widget’s build() method. Therefore it is

important that build methods should return quickly, and heavy computational work

should be done in some asynchronous manner and then stored as part of the state

to be used by a build method.

While relatively naïve in approach, this automated comparison is quite effective, enabling high-performance, interactive apps. And, the design of the build function simplifies your code by focusing on declaring what a widget is made of, rather than the complexities of updating the user interface from one state to another.

Widget state

The framework introduces two major classes of widget: stateful and stateless widgets.

Many widgets have no mutable state: they don’t have any properties that change

over time (for example, an icon or a label). These widgets subclass

StatelessWidget.

However, if the unique characteristics of a widget need to change based on user

interaction or other factors, that widget is stateful. For example, if a

widget has a counter that increments whenever the user taps a button, then the

value of the counter is the state for that widget. When that value changes, the

widget needs to be rebuilt to update its part of the UI. These widgets subclass

StatefulWidget, and

(because the widget itself is immutable) they store mutable state in a separate

class that subclasses State.

StatefulWidgets don’t have a build method; instead, their user interface is

built through their State object.

Whenever you mutate a State object (for example, by incrementing the counter),

you must call setState()

to signal the framework to update the user interface by calling the State’s

build method again.

Having separate state and widget objects lets other widgets treat both stateless and stateful widgets in exactly the same way, without being concerned about losing state. Instead of needing to hold on to a child to preserve its state, the parent can create a new instance of the child at any time without losing the child’s persistent state. The framework does all the work of finding and reusing existing state objects when appropriate.

State management

So, if many widgets can contain state, how is state managed and passed around the system?

As with any other class, you can use a constructor in a widget to initialize its

data, so a build() method can ensure that any child widget is instantiated

with the data it needs:

@override

Widget build(BuildContext context) {

return ContentWidget(importantState);

}

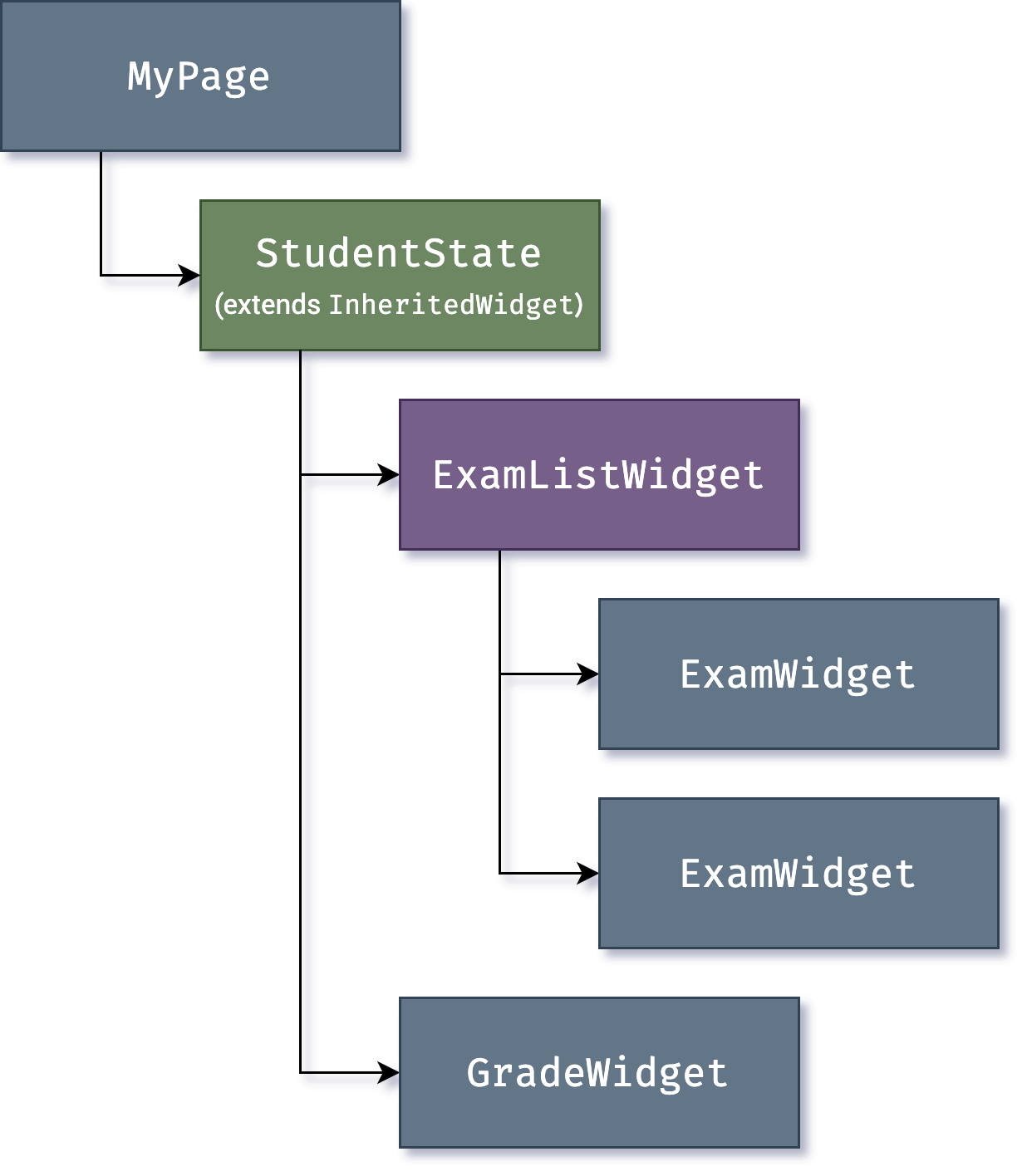

As widget trees get deeper, however, passing state information up and down the

tree hierarchy becomes cumbersome. So, a third widget type,

InheritedWidget,

provides an easy way to grab data from a shared ancestor. You can use

InheritedWidget to create a state widget that wraps a common ancestor in the

widget tree, as shown in this example:

Whenever one of the ExamWidget or GradeWidget objects needs data from

StudentState, it can now access it with a command such as:

final studentState = StudentState.of(context);

The of(context) call takes the build context (a handle to the current widget

location), and returns the nearest ancestor in the

tree

that matches the StudentState type. InheritedWidgets also offer an

updateShouldNotify() method, which Flutter calls to determine whether a state

change should trigger a rebuild of child widgets that use it.

Flutter itself uses InheritedWidget extensively as part of the framework for

shared state, such as the application’s visual theme, which includes

properties like color and type

styles that are

pervasive throughout an application. The MaterialApp build() method inserts

a theme in the tree when it builds, and then deeper in the hierarchy a widget

can use the .of() method to look up the relevant theme data, for example:

Container(

color: Theme.of(context).secondaryHeaderColor,

child: Text(

'Text with a background color',

style: Theme.of(context).textTheme.headline6,

),

);This approach is also used for Navigator, which provides page routing; and MediaQuery, which provides access to screen metrics such as orientation, dimensions, and brightness.

As applications grow, more advanced state management approaches that reduce the

ceremony of creating and using stateful widgets become more attractive. Many

Flutter apps use utility packages like

provider, which provides a wrapper around

InheritedWidget. Flutter’s layered architecture also enables alternative

approaches to implement the transformation of state into UI, such as the

flutter_hooks package.

Rendering and layout

This section describes the rendering pipeline, which is the series of steps that Flutter takes to convert a hierarchy of widgets into the actual pixels painted onto a screen.

Flutter’s rendering model

You may be wondering: if Flutter is a cross-platform framework, then how can it offer comparable performance to single-platform frameworks?

It’s useful to start by thinking about how traditional Android apps work. When drawing, you first call the Java code of the Android framework. The Android system libraries provide the components responsible for drawing themselves to a Canvas object, which Android can then render with Skia, a graphics engine written in C/C++ that calls the CPU or GPU to complete the drawing on the device.

Cross-platform frameworks typically work by creating an abstraction layer over the underlying native Android and iOS UI libraries, attempting to smooth out the inconsistencies of each platform representation. App code is often written in an interpreted language like JavaScript, which must in turn interact with the Java-based Android or Objective-C-based iOS system libraries to display UI. All this adds overhead that can be significant, particularly where there is a lot of interaction between the UI and the app logic.

By contrast, Flutter minimizes those abstractions, bypassing the system UI widget libraries in favor of its own widget set. The Dart code that paints Flutter’s visuals is compiled into native code, which uses Skia for rendering. Flutter also embeds its own copy of Skia as part of the engine, allowing the developer to upgrade their app to stay updated with the latest performance improvements even if the phone hasn’t been updated with a new Android version. The same is true for Flutter on other native platforms, such as iOS, Windows, or macOS.

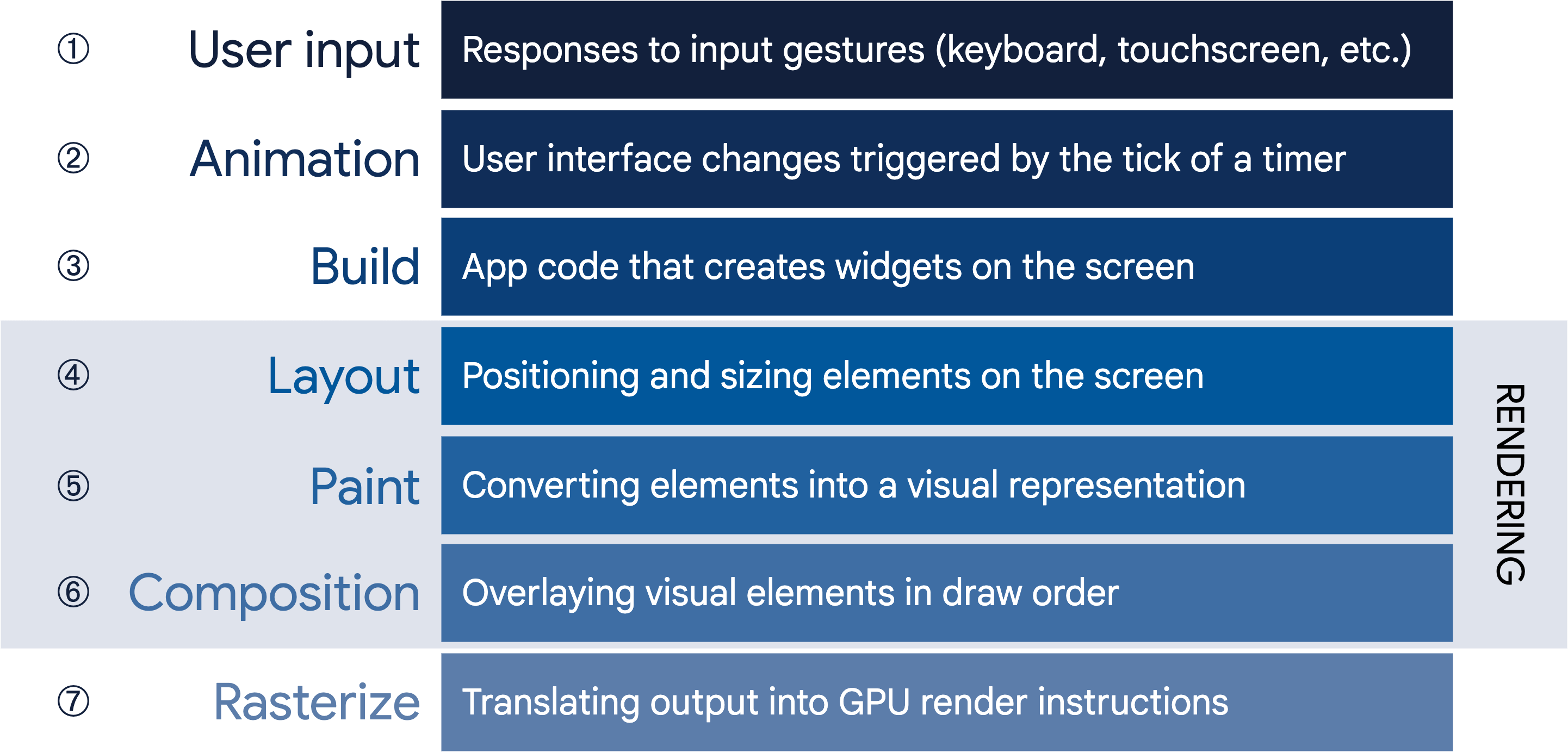

From user input to the GPU

The overriding principle that Flutter applies to its rendering pipeline is that simple is fast. Flutter has a straightforward pipeline for how data flows to the system, as shown in the following sequencing diagram:

Let’s take a look at some of these phases in greater detail.

Build: from Widget to Element

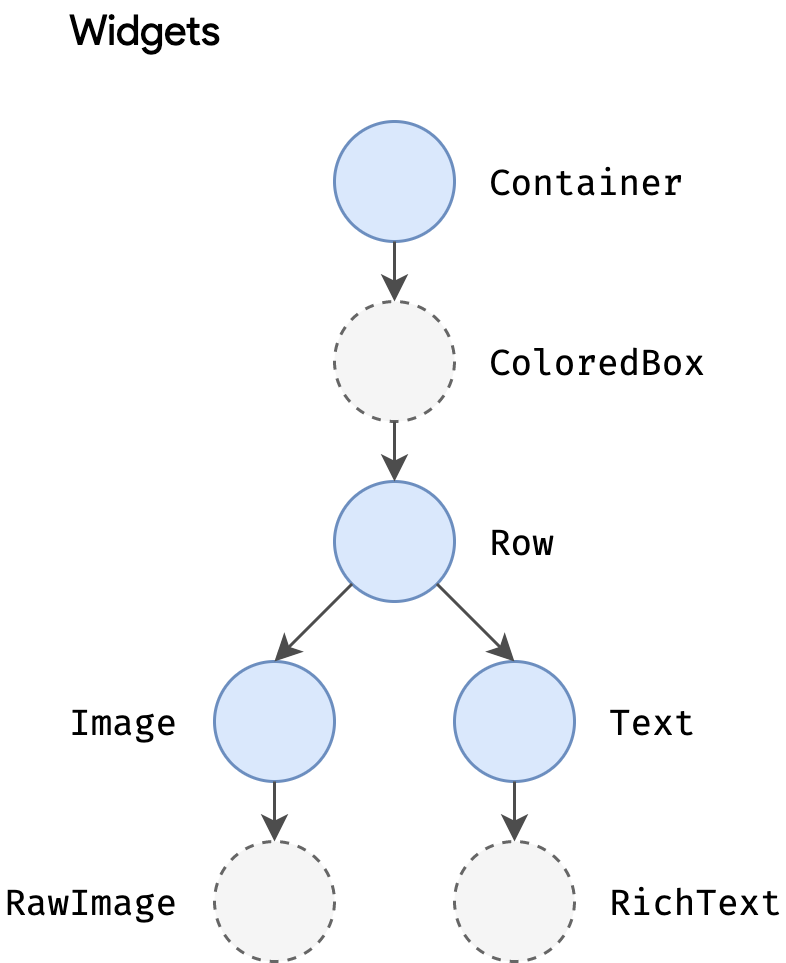

Consider this simple code fragment that demonstrates a simple widget hierarchy:

Container(

color: Colors.blue,

child: Row(

children: [

Image.network('https://www.example.com/1.png'),

const Text('A'),

],

),

);When Flutter needs to render this fragment, it calls the build() method, which

returns a subtree of widgets that renders UI based on the current app state.

During this process, the build() method can introduce new widgets, as

necessary, based on its state. As a simple example, in the preceding code

fragment, Container has color and child properties. From looking at the

source

code

for Container, you can see that if the color is not null, it inserts a

ColoredBox representing the color:

if (color != null)

current = ColoredBox(color: color!, child: current);

Correspondingly, the Image and Text widgets might insert child widgets such

as RawImage and RichText during the build process. The eventual widget

hierarchy may therefore be deeper than what the code represents, as in this

case2:

This explains why, when you examine the tree through a debug tool such as the Flutter inspector, part of the Dart DevTools, you might see a structure that is considerably deeper than what is in your original code.

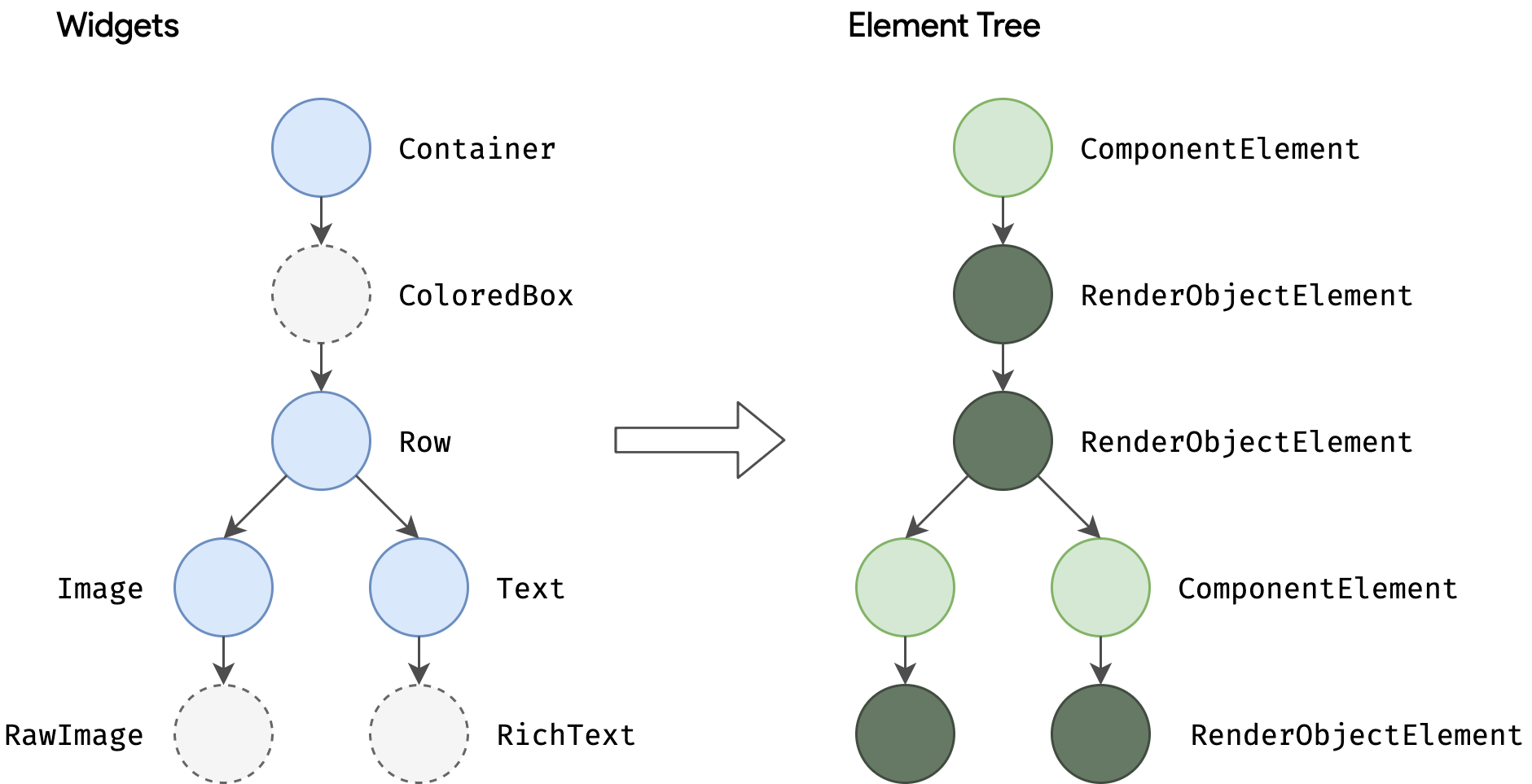

During the build phase, Flutter translates the widgets expressed in code into a corresponding element tree, with one element for every widget. Each element represents a specific instance of a widget in a given location of the tree hierarchy. There are two basic types of elements:

-

ComponentElement, a host for other elements. -

RenderObjectElement, an element that participates in the layout or paint phases.

RenderObjectElements are an intermediary between their widget analog and the

underlying RenderObject, which we’ll come to later.

The element for any widget can be referenced through its BuildContext, which

is a handle to the location of a widget in the tree. This is the context in a

function call such as Theme.of(context), and is supplied to the build()

method as a parameter.

Because widgets are immutable, including the parent/child relationship between

nodes, any change to the widget tree (such as changing Text('A') to

Text('B') in the preceding example) causes a new set of widget objects to be

returned. But that doesn’t mean the underlying representation must be rebuilt.

The element tree is persistent from frame to frame, and therefore plays a

critical performance role, allowing Flutter to act as if the widget hierarchy is

fully disposable while caching its underlying representation. By only walking

through the widgets that changed, Flutter can rebuild just the parts of the

element tree that require reconfiguration.

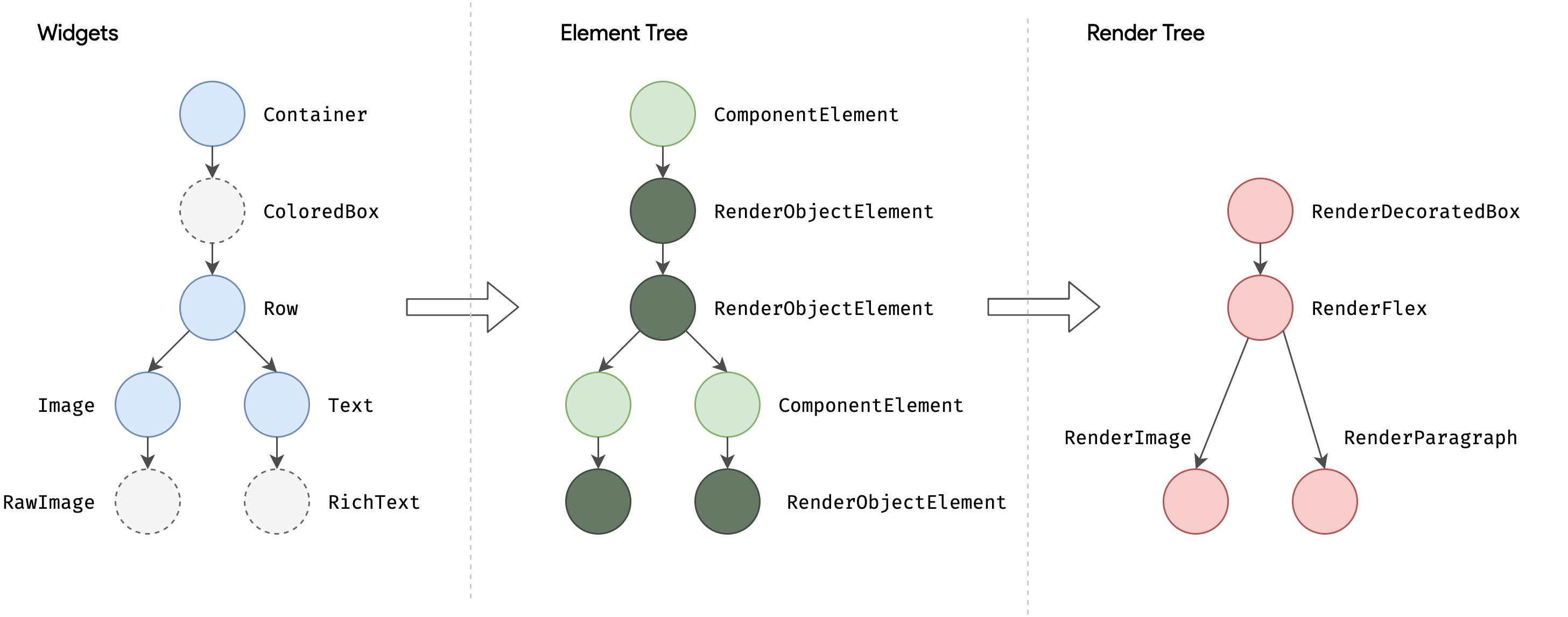

Layout and rendering

It would be a rare application that drew only a single widget. An important part of any UI framework is therefore the ability to efficiently lay out a hierarchy of widgets, determining the size and position of each element before they are rendered on the screen.

The base class for every node in the render tree is

RenderObject, which

defines an abstract model for layout and painting. This is extremely general: it

does not commit to a fixed number of dimensions or even a Cartesian coordinate

system (demonstrated by this example of a polar coordinate

system). Each

RenderObject knows its parent, but knows little about its children other than

how to visit them and their constraints. This provides RenderObject with

sufficient abstraction to be able to handle a variety of use cases.

During the build phase, Flutter creates or updates an object that inherits from

RenderObject for each RenderObjectElement in the element tree.

RenderObjects are primitives:

RenderParagraph

renders text,

RenderImage renders

an image, and

RenderTransform

applies a transformation before painting its child.

Most Flutter widgets are rendered by an object that inherits from the

RenderBox subclass, which represents a RenderObject of fixed size in a 2D

Cartesian space. RenderBox provides the basis of a box constraint model,

establishing a minimum and maximum width and height for each widget to be

rendered.

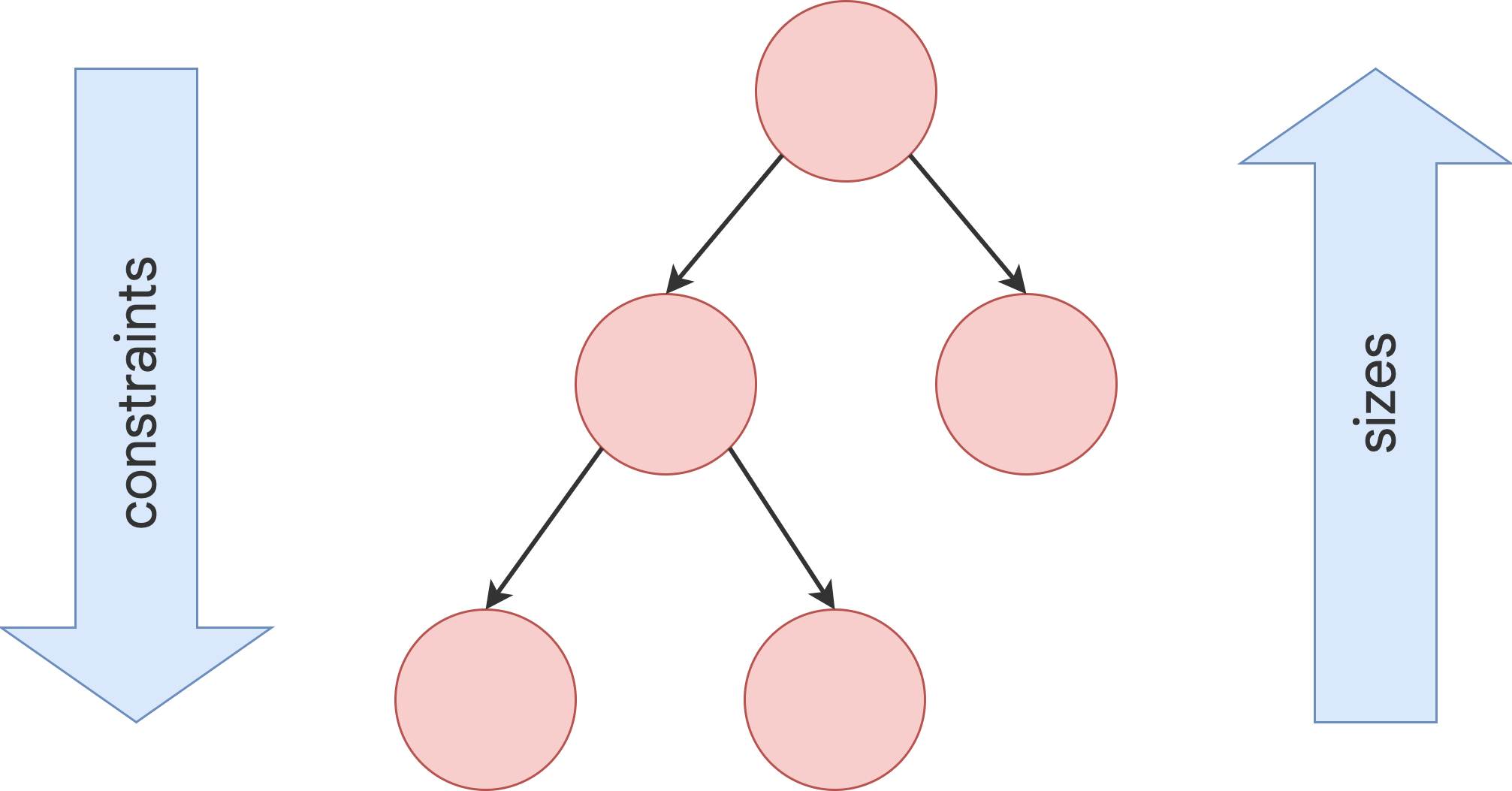

To perform layout, Flutter walks the render tree in a depth-first traversal and passes down size constraints from parent to child. In determining its size, the child must respect the constraints given to it by its parent. Children respond by passing up a size to their parent object within the constraints the parent established.

At the end of this single walk through the tree, every object has a defined size

within its parent’s constraints and is ready to be painted by calling the

paint()

method.

The box constraint model is very powerful as a way to layout objects in O(n) time:

- Parents can dictate the size of a child object by setting maximum and minimum constraints to the same value. For example, the topmost render object in a phone app constrains its child to be the size of the screen. (Children can choose how to use that space. For example, they might just center what they want to render within the dictated constraints.)

- A parent can dictate the child’s width but give the child flexibility over height (or dictate height but offer flexible over width). A real-world example is flow text, which might have to fit a horizontal constraint but vary vertically depending on the quantity of text.

This model works even when a child object needs to know how much space it has

available to decide how it will render its content. By using a

LayoutBuilder widget,

the child object can examine the passed-down constraints and use those to

determine how it will use them, for example:

Widget build(BuildContext context) {

return LayoutBuilder(

builder: (context, constraints) {

if (constraints.maxWidth < 600) {

return const OneColumnLayout();

} else {

return const TwoColumnLayout();

}

},

);

}More information about the constraint and layout system, along with worked examples, can be found in the Understanding constraints topic.

The root of all RenderObjects is the RenderView, which represents the total

output of the render tree. When the platform demands a new frame to be rendered

(for example, because of a

vsync or because

a texture decompression/upload is complete), a call is made to the

compositeFrame() method, which is part of the RenderView object at the root

of the render tree. This creates a SceneBuilder to trigger an update of the

scene. When the scene is complete, the RenderView object passes the composited

scene to the Window.render() method in dart:ui, which passes control to the

GPU to render it.

Further details of the composition and rasterization stages of the pipeline are beyond the scope of this high-level article, but more information can be found in this talk on the Flutter rendering pipeline.

Platform embedding

As we’ve seen, rather than being translated into the equivalent OS widgets, Flutter user interfaces are built, laid out, composited, and painted by Flutter itself. The mechanism for obtaining the texture and participating in the app lifecycle of the underlying operating system inevitably varies depending on the unique concerns of that platform. The engine is platform-agnostic, presenting a stable ABI (Application Binary Interface) that provides a platform embedder with a way to set up and use Flutter.

The platform embedder is the native OS application that hosts all Flutter content, and acts as the glue between the host operating system and Flutter. When you start a Flutter app, the embedder provides the entrypoint, initializes the Flutter engine, obtains threads for UI and rastering, and creates a texture that Flutter can write to. The embedder is also responsible for the app lifecycle, including input gestures (such as mouse, keyboard, touch), window sizing, thread management, and platform messages. Flutter includes platform embedders for Android, iOS, Windows, macOS, and Linux; you can also create a custom platform embedder, as in this worked example that supports remoting Flutter sessions through a VNC-style framebuffer or this worked example for Raspberry Pi.

Each platform has its own set of APIs and constraints. Some brief platform-specific notes:

- On iOS and macOS, Flutter is loaded into the embedder as a

UIViewControllerorNSViewController, respectively. The platform embedder creates aFlutterEngine, which serves as a host to the Dart VM and your Flutter runtime, and aFlutterViewController, which attaches to theFlutterEngineto pass UIKit or Cocoa input events into Flutter and to display frames rendered by theFlutterEngineusing Metal or OpenGL. - On Android, Flutter is, by default, loaded into the embedder as an

Activity. The view is controlled by aFlutterView, which renders Flutter content either as a view or a texture, depending on the composition and z-ordering requirements of the Flutter content. - On Windows, Flutter is hosted in a traditional Win32 app, and content is rendered using ANGLE, a library that translates OpenGL API calls to the DirectX 11 equivalents. Efforts are currently underway to also offer a Windows embedder using the UWP app model, as well as to replace ANGLE with a more direct path to the GPU via DirectX 12.

Integrating with other code

Flutter provides a variety of interoperability mechanisms, whether you’re accessing code or APIs written in a language like Kotlin or Swift, calling a native C-based API, embedding native controls in a Flutter app, or embedding Flutter in an existing application.

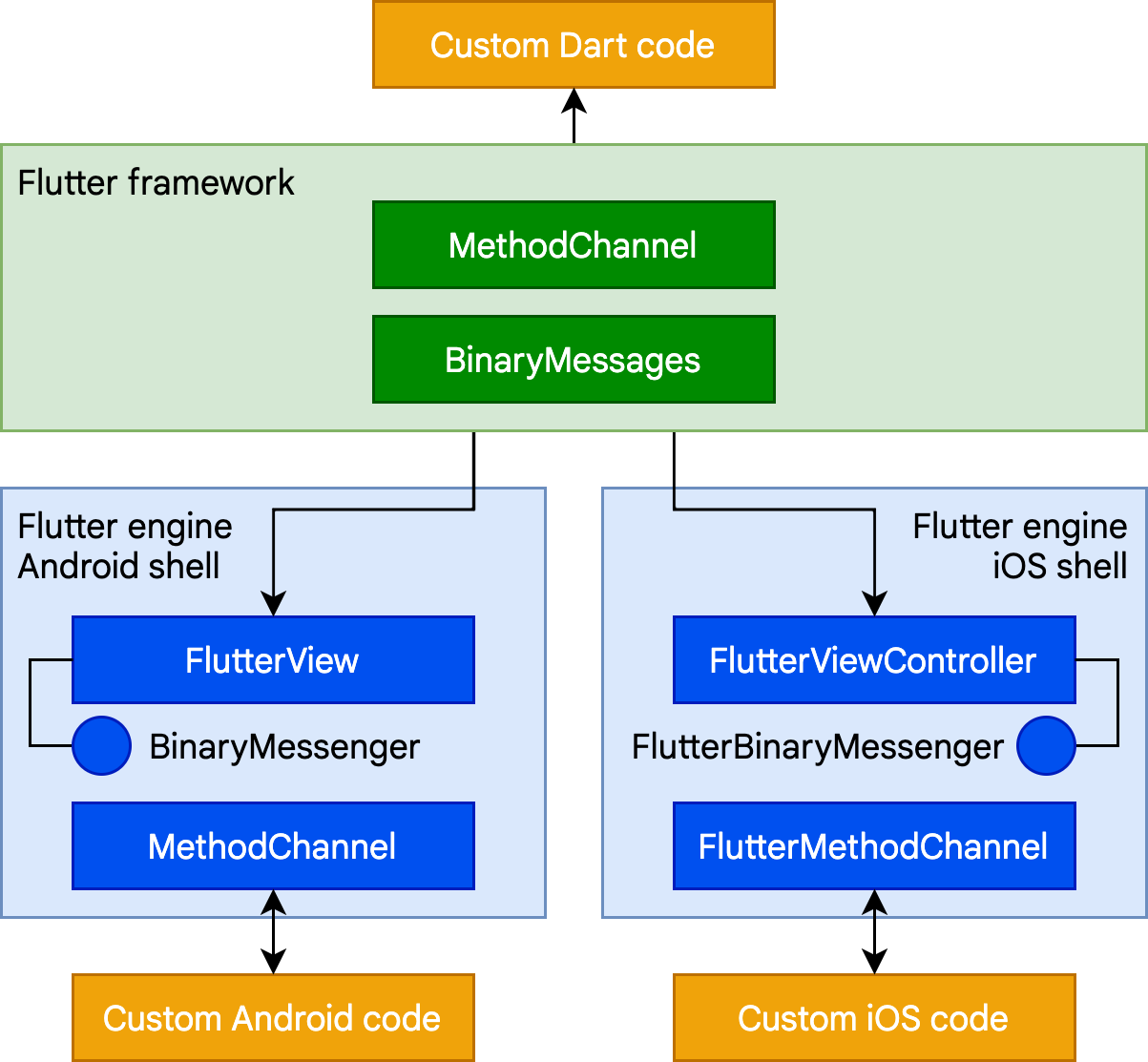

Platform channels

For mobile and desktop apps, Flutter allows you to call into custom code through

a platform channel, which is a simple mechanism for communicating between your

Dart code and the platform-specific code of your host app. By creating a common

channel (encapsulating a name and a codec), you can send and receive messages

between Dart and a platform component written in a language like Kotlin or

Swift. Data is serialized from a Dart type like Map into a standard format,

and then deserialized into an equivalent representation in Kotlin (such as

HashMap) or Swift (such as Dictionary).

The following is a simple platform channel example of a Dart call to a receiving event handler in Kotlin (Android) or Swift (iOS):

// Dart side

const channel = MethodChannel('foo');

final String greeting = await channel.invokeMethod('bar', 'world');

print(greeting);// Android (Kotlin)

val channel = MethodChannel(flutterView, "foo")

channel.setMethodCallHandler { call, result ->

when (call.method) {

"bar" -> result.success("Hello, ${call.arguments}")

else -> result.notImplemented()

}

}

// iOS (Swift)

let channel = FlutterMethodChannel(name: "foo", binaryMessenger: flutterView)

channel.setMethodCallHandler {

(call: FlutterMethodCall, result: FlutterResult) -> Void in

switch (call.method) {

case "bar": result("Hello, \(call.arguments as! String)")

default: result(FlutterMethodNotImplemented)

}

}

Further examples of using platform channels, including examples for macOS, can be found in the flutter/plugins repository3. There are also thousands of plugins already available for Flutter that cover many common scenarios, ranging from Firebase to ads to device hardware like camera and Bluetooth.

Foreign Function Interface

For C-based APIs, including those that can be generated for code written in

modern languages like Rust or Go, Dart provides a direct mechanism for binding

to native code using the dart:ffi library. The foreign function interface

(FFI) model can be considerably faster than platform channels, because no

serialization is required to pass data. Instead, the Dart runtime provides the

ability to allocate memory on the heap that is backed by a Dart object and make

calls to statically or dynamically linked libraries. FFI is available for all

platforms other than web, where the js package

serves an equivalent purpose.

To use FFI, you create a typedef for each of the Dart and unmanaged method

signatures, and instruct the Dart VM to map between them. As a simple example,

here’s a fragment of code to call the traditional Win32 MessageBox() API:

typedef MessageBoxNative = Int32 Function(

IntPtr hWnd,

Pointer<Utf16> lpText,

Pointer<Utf16> lpCaption,

Int32 uType,

);

typedef MessageBoxDart = int Function(

int hWnd,

Pointer<Utf16> lpText,

Pointer<Utf16> lpCaption,

int uType,

);

void exampleFfi() {

final user32 = DynamicLibrary.open('user32.dll');

final messageBox =

user32.lookupFunction<MessageBoxNative, MessageBoxDart>('MessageBoxW');

final result = messageBox(

0, // No owner window

'Test message'.toNativeUtf16(), // Message

'Window caption'.toNativeUtf16(), // Window title

0, // OK button only

);

}Rendering native controls in a Flutter app

Because Flutter content is drawn to a texture and its widget tree is entirely internal, there’s no place for something like an Android view to exist within Flutter’s internal model or render interleaved within Flutter widgets. That’s a problem for developers that would like to include existing platform components in their Flutter apps, such as a browser control.

Flutter solves this by introducing platform view widgets

(AndroidView

and UiKitView)

that let you embed this kind of content on each platform. Platform views can be

integrated with other Flutter content4. Each of

these widgets acts as an intermediary to the underlying operating system. For

example, on Android, AndroidView serves three primary functions:

- Making a copy of the graphics texture rendered by the native view and presenting it to Flutter for composition as part of a Flutter-rendered surface each time the frame is painted.

- Responding to hit testing and input gestures, and translating those into the equivalent native input.

- Creating an analog of the accessibility tree, and passing commands and responses between the native and Flutter layers.

Inevitably, there is a certain amount of overhead associated with this synchronization. In general, therefore, this approach is best suited for complex controls like Google Maps where reimplementing in Flutter isn’t practical.

Typically, a Flutter app instantiates these widgets in a build() method based

on a platform test. As an example, from the

google_maps_flutter plugin:

if (defaultTargetPlatform == TargetPlatform.android) {

return AndroidView(

viewType: 'plugins.flutter.io/google_maps',

onPlatformViewCreated: onPlatformViewCreated,

gestureRecognizers: gestureRecognizers,

creationParams: creationParams,

creationParamsCodec: const StandardMessageCodec(),

);

} else if (defaultTargetPlatform == TargetPlatform.iOS) {

return UiKitView(

viewType: 'plugins.flutter.io/google_maps',

onPlatformViewCreated: onPlatformViewCreated,

gestureRecognizers: gestureRecognizers,

creationParams: creationParams,

creationParamsCodec: const StandardMessageCodec(),

);

}

return Text(

'$defaultTargetPlatform is not yet supported by the maps plugin');

Communicating with the native code underlying the AndroidView or UiKitView

typically occurs using the platform channels mechanism, as previously described.

At present, platform views aren’t available for desktop platforms, but this is not an architectural limitation; support might be added in the future.

Hosting Flutter content in a parent app

The converse of the preceding scenario is embedding a Flutter widget in an

existing Android or iOS app. As described in an earlier section, a newly created

Flutter app running on a mobile device is hosted in an Android activity or iOS

UIViewController. Flutter content can be embedded into an existing Android or

iOS app using the same embedding API.

The Flutter module template is designed for easy embedding; you can either embed it as a source dependency into an existing Gradle or Xcode build definition, or you can compile it into an Android Archive or iOS Framework binary for use without requiring every developer to have Flutter installed.

The Flutter engine takes a short while to initialize, because it needs to load Flutter shared libraries, initialize the Dart runtime, create and run a Dart isolate, and attach a rendering surface to the UI. To minimize any UI delays when presenting Flutter content, it’s best to initialize the Flutter engine during the overall app initialization sequence, or at least ahead of the first Flutter screen, so that users don’t experience a sudden pause while the first Flutter code is loaded. In addition, separating the Flutter engine allows it to be reused across multiple Flutter screens and share the memory overhead involved with loading the necessary libraries.

More information about how Flutter is loaded into an existing Android or iOS app can be found at the Load sequence, performance and memory topic.

Flutter web support

While the general architectural concepts apply to all platforms that Flutter supports, there are some unique characteristics of Flutter’s web support that are worthy of comment.

Dart has been compiling to JavaScript for as long as the language has existed, with a toolchain optimized for both development and production purposes. Many important apps compile from Dart to JavaScript and run in production today, including the advertiser tooling for Google Ads. Because the Flutter framework is written in Dart, compiling it to JavaScript was relatively straightforward.

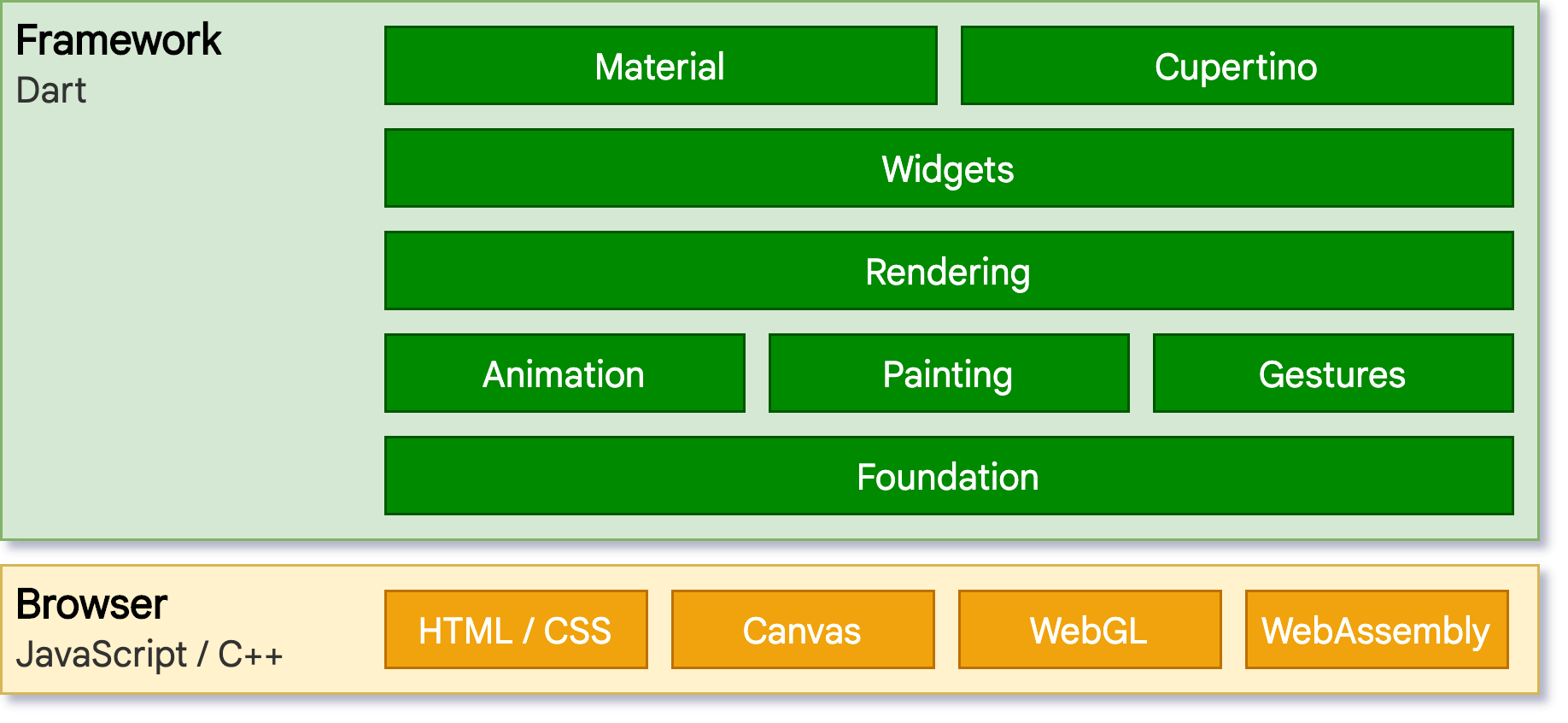

However, the Flutter engine, written in C++, is designed to interface with the underlying operating system rather than a web browser. A different approach is therefore required. On the web, Flutter provides a reimplementation of the engine on top of standard browser APIs. We currently have two options for rendering Flutter content on the web: HTML and WebGL. In HTML mode, Flutter uses HTML, CSS, Canvas, and SVG. To render to WebGL, Flutter uses a version of Skia compiled to WebAssembly called CanvasKit. While HTML mode offers the best code size characteristics, CanvasKit provides the fastest path to the browser’s graphics stack, and offers somewhat higher graphical fidelity with the native mobile targets5.

The web version of the architectural layer diagram is as follows:

Perhaps the most notable difference compared to other platforms on which Flutter runs is that there is no need for Flutter to provide a Dart runtime. Instead, the Flutter framework (along with any code you write) is compiled to JavaScript. It’s also worthy to note that Dart has very few language semantic differences across all its modes (JIT versus AOT, native versus web compilation), and most developers will never write a line of code that runs into such a difference.

During development time, Flutter web uses

dartdevc, a compiler that supports

incremental compilation and therefore allows hot restart (although not currently

hot reload) for apps. Conversely, when you are ready to create a production app

for the web, dart2js, Dart’s

highly-optimized production JavaScript compiler is used, packaging the Flutter

core and framework along with your application into a minified source file that

can be deployed to any web server. Code can be offered in a single file or split

into multiple files through deferred

imports.

Further information

For those interested in more information about the internals of Flutter, the Inside Flutter whitepaper provides a useful guide to the framework’s design philosophy.

Footnotes:

1 While the build function returns a fresh tree,

you only need to return something different if there’s some new

configuration to incorporate. If the configuration is in fact the same, you can

just return the same widget.

2 This is a slight simplification for ease of reading. In practice, the tree might be more complex.

3 While work is underway on Linux and Windows, examples for those platforms can be found in the Flutter desktop embedding repository. As development on those platforms reaches maturity, this content will be gradually migrated into the main Flutter repository.

4 There are some limitations with this approach, for example, transparency doesn’t composite the same way for a platform view as it would for other Flutter widgets.

5 One example is shadows, which have to be approximated with DOM-equivalent primitives at the cost of some fidelity.